These are not peace terms. They amount instead to the penalties that a triumphant power extracts from a defeated opponent. Restrictions on the size of the Ukrainian army. A prohibition on Nato entry. No Western troops stationed in Ukraine. No US aircraft operating even in nearby Poland. Fresh elections aimed at ousting Volodymyr Zelensky.

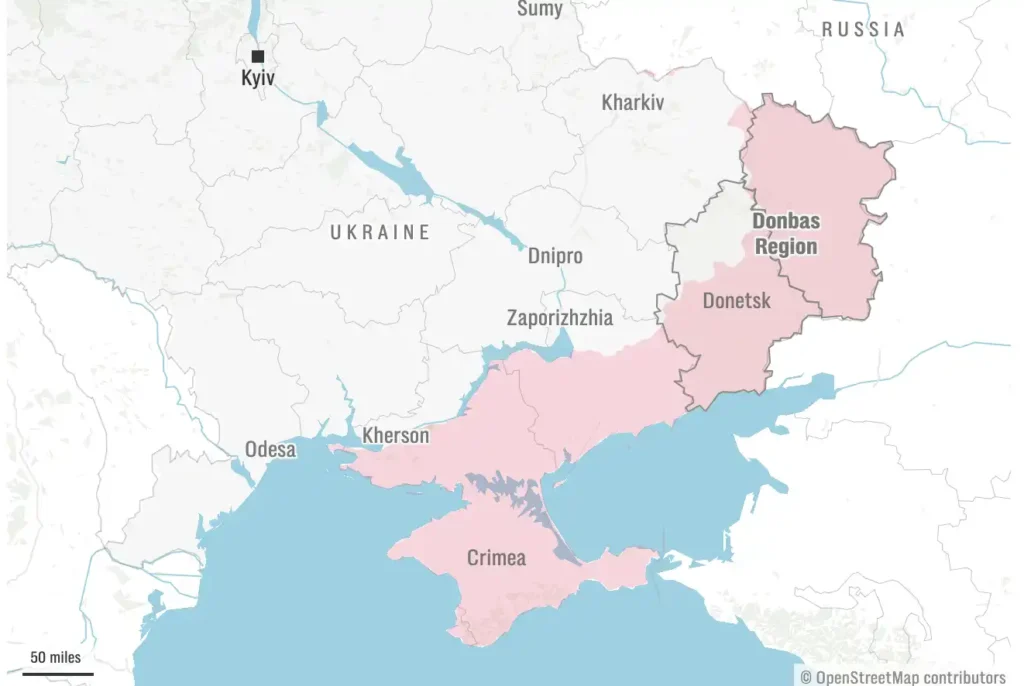

Russia will relinquish none of the territory it seized illegally. It will not even limit itself to the current areas of control. Rather, it will effectively be granted additional Ukrainian land, securing formal control over the full Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts and acquiring roughly 250,000 new citizens.

Luhansk is, in fairness, already mostly occupied by Moscow, with Ukraine hanging on to only a small number of frontier villages. But the dividing line in Donetsk has stayed roughly the same since the conflict ignited in 2014. Giving up the Ukrainian-held areas there would mean surrendering the nation’s most crucial defensive positions, much as Czechoslovakia was compelled to hand over its fortified border regions in 1938.

I am not normally inclined toward Second World War comparisons, and I have never previously invoked Munich in a column, yet the echoes this time are impossible to overlook. Russian-speaking residents in the Donbas were agitated in precisely the way ethnic Germans in Czechoslovakia once were. Volodymyr Zelensky offered moderate territorial compromises to Putin in the early stages of the conflict, just as Edvard Beneš had proposed transferring several thousand square miles of Czech territory to Germany.

In both instances, however, the eventual agreement was arranged by others over the remains of the country being offered up. Just as Beneš stepped down after the Munich deal, it now seems unimaginable that Zelensky — already weakened by backlash over his autocratic reaction to corruption allegations — can remain in office.

We all know the aftermath of Munich. Six months after declaring that Germany’s claims were fully and finally met, Hitler seized the rest of the Czech state, folding it into the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia.

Does Putin envision one day restarting hostilities with a diminished Ukraine, one prohibited by agreement from joining the Western alliance? And if he did resume attacks, who exactly would be positioned to intervene? After Munich, Europe no longer misunderstood the danger Hitler represented, and Chamberlain used the respite to massively boost aircraft production. Putin, in stark contrast, is to be welcomed back into the international fold, his frozen assets restored, and his country potentially invited to turn the G7 back into the G8 — a privilege Russia’s economy and political system hardly justify.

Perhaps Ukrainians, worn out and dispirited, will accept these demands as the baseline for ceasefire talks. Their alternatives are bleak. They could attempt to fight on without US weapons or ammunition, while European nations empty their already depleted stockpiles to compensate. But they cannot endure the loss of American intelligence and satellite data, which they rely on for targeting, warnings, and reconnaissance.

Trump shut off intelligence sharing in March, but reversed course a week later after pushback from his generals and then-national security adviser Mike Waltz, the highly regarded former special forces officer. Alarmingly, the civilian and military figures who advised against the shutdown have since been removed, suggesting the next cutoff would be permanent.

So much for the narrative that the US is merely avoiding intervention or trimming expenses. Intelligence sharing costs almost nothing, and the US could simply sell equipment to Europe for Ukrainian use. This is not about frugality or isolationism. It is choosing a side — Putin’s side. The US and Russia are both poised to take advantage of the energy reserves and assets of a devastated former American ally.

We have returned to precisely the point many feared the moment Donald Trump captured the 2024 election. Any façade of impartiality has vanished. Those stern warnings of “very severe consequences” if Putin rejected a ceasefire at the Alaska summit now look hollow. As I have regretfully written before, I don’t subscribe to the claims that Putin holds kompromat over Trump; yet the bleak reality is that, with or without such leverage, Trump is acting exactly as he would if he were a Russian asset.

The US and Russia carried out negotiations entirely on their own, excluding not only Ukraine but every other stakeholder — especially Britain, Ukraine’s earliest and firmest supporter. Representing Trump in these talks was the unimpressive and hopelessly out-of-his-depth Steve Witkoff, a New York property developer who, in a painful Tucker Carlson interview, couldn’t name a single Ukrainian region under discussion and gushed over the “beautiful portrait” of Trump gifted to him by a Kremlin oligarch mimicking his American counterpart.

This is not only a catastrophe for Ukraine, a nation that has already endured more than enough in the past century. It is an immediate strategic crisis for Britain, now left abruptly separated from the ally it has relied upon since 1941.

Was it a coincidence that, just as the 28-point capitulation framework became public, a Russian spy ship in British waters directed military-grade lasers at UK pilots? Possibly. Defence Secretary John Healey may have exaggerated the event to polish his leadership prospects. But I doubt it. Far more plausibly, Putin was flaunting and taunting — flaunting his gains in Ukraine and taunting the nation he resents more than any other.

To understand Putin’s thinking, it helps to heed his deputy, Dmitry Medvedev, who trails behind him like a hunched Igor in service to a gothic villain. Medvedev, always ready to say the quiet parts aloud, labels Britain “Moscow’s eternal enemy” and declares that “we need to solve the problem at its root and immediately sink the damned island of Anglo-Saxon dogs”.

Where does such animosity originate? Some argue that Putin never forgave British special forces for eliminating his allies in Syria; others believe his bitterness dates back to being thwarted by MI6 during his KGB days in East Germany. It may stem from London’s long-standing role as the refuge of anti-Putin dissidents, who sought safety in one of the few places where judges and police chiefs could not be bribed. Or perhaps it traces back to the Great Game of the 19th century — a history Putin, evidently spending lockdown reading mediocre historical texts, seems intimately familiar with.

Whatever the case, the Ukraine peace arrangement amounts to nearly as grave a setback for Britain as for Ukraine. Since 1956, Britain has coordinated major military deployments with the United States. The partnership is not as lopsided as critics suggest: Britain has gained enormously from America’s willingness to share intelligence and nuclear capabilities — privileges extended to no other nation. Now, without warning, that alliance appears fragile and conditional.

More troubling still is what this means for the world order that alliance has upheld since the Atlantic Charter of 1941 — an order rooted in the idea that borders should not be altered by violence, that democracy is superior to tyranny, and that the rule of law should govern relations both within and between states.

How has such a system been undone by a country that, even before the war, had an economy smaller than Italy’s, and has since lost millions to emigration and battlefield deaths, not to mention hundreds of billions of roubles siphoned off through corruption?

The answer is stark: it has fallen not due to an external adversary, but because of a shift from within. It has been defeated not by Putin, but by Trump. Western societies have done this to themselves. And our children will one day regret it.