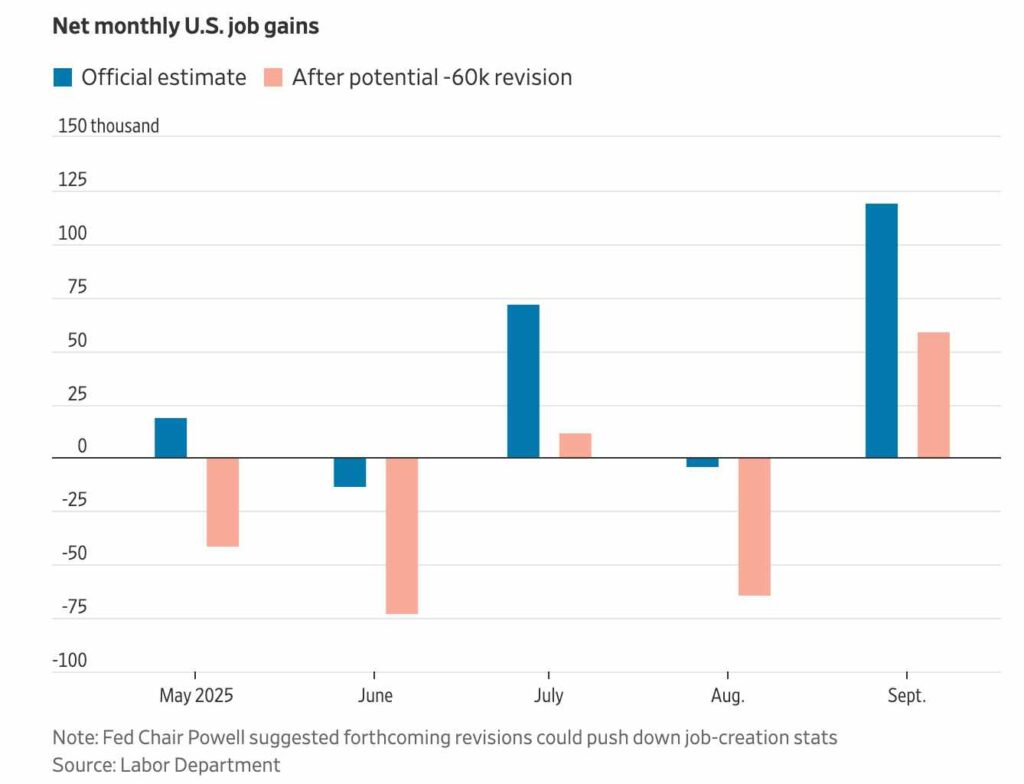

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell on Wednesday highlighted a major labor-market risk that economists have been warning about for months: official hiring data may be significantly overstated. Powell said Fed analysts believe federal statistics may be inflating job creation by as much as 60,000 positions per month. Since published figures show the economy gaining roughly 40,000 jobs monthly since April, he suggested the real number could actually reflect a loss of about 20,000 jobs each month. “We think there’s an overstatement in these numbers,” Powell explained during a press briefing after the Fed’s two-day policy meeting.

Even the already-reported slowdown in hiring this year, following the rapid post-pandemic rebound, means that any substantial revisions could push the data into negative territory. “It’s a complicated, unusual, and difficult situation, where the labor market is also under pressure, where job creation may actually be negative,” Powell said. This concern helped justify the Fed’s decision to cut interest rates for the third consecutive meeting, he noted, even though the broader labor picture still appears steady on the surface, with unemployment at 4.4% in September and an official gain of 119,000 jobs that month. The Labor Department is expected to publish new figures for October and November next week, including revisions to earlier months.

Powell’s comments point to a long-running challenge inside the Labor Department: attempting to estimate job changes at newly formed or recently closed businesses. Because federal statisticians cannot reliably survey brand-new firms or those that have already shut down, the Bureau of Labor Statistics uses a statistical tool known as the birth-death model to estimate the effects of business openings and closures. In recent years, that model has led to large overstatements—hundreds of thousands of jobs annually—which later had to be corrected downward.

The BLS said last month that it plans to revise how the birth-death model is used, a change that could make real-time data more accurate beginning in February. But for now, Powell indicated the Fed is wary that monthly employment reports may have been overly optimistic, which is part of the reasoning behind continued rate cuts even though inflation remains above target.

Beyond the model itself, the BLS has been dealing with several other problems that have made its job harder. Declining response rates to labor surveys have increased the magnitude of subsequent revisions, as more employers file their payroll information late. Years of budget pressures and staffing shortages have also strained the agency’s operations, and the prolonged government shutdown that finally ended in November set back its work by more than a month.

These complications have even spilled into national politics. President Trump blamed the data difficulties on what he alleged were efforts to manipulate statistics for political motives, and he dismissed BLS Commissioner Erika McEntarfer after major revisions in August reduced reported spring hiring. The agency is now being run by a nonpartisan career official serving in an acting capacity.

Fed Chair Jerome Powell said that Fed staffers believe federal data could be overstating job creation by up to 60,000 jobs a month—which suggests the jobs market might be shrinking https://t.co/B3XAr9st02

— The Wall Street Journal (@WSJ) December 11, 2025